Write the way you talk—your family will thank you

One reason that life story books that derive from personal history interviews are often so compelling is that they reveal the subject’s true voice.

Picture it: An interviewer and a subject settle in for some reminiscing. Perhaps the story sharing is stilted at first. Then a comfort level is established and a rhythm is found and stories flow—and the storyteller, free of pretenses, sounds just like they always do. Maybe a little more animated (it’s exciting sharing all those memories!) or a little more sentimental (again, those memories!!), but like them.

If that same individual sat down to write their stories, though, all too often their voice would get lost. Even the most seasoned writers can spend too much time focusing on making things sound “writerly” at the expense of sounding natural.

Reading work that is written with a disregard for one’s own voice can feel labored—but mostly, it can feel like we’re hearing from someone we’ve never met. Where is the Aunt Ida you know and love amidst all those flowery adjectives and semi-coloned sentences? What happened to Grandmom’s penchant for punctuating her thoughts with cuss words? How about the southern idioms that Pop usually wields—without them it’s as if he’s speaking a different language altogether.

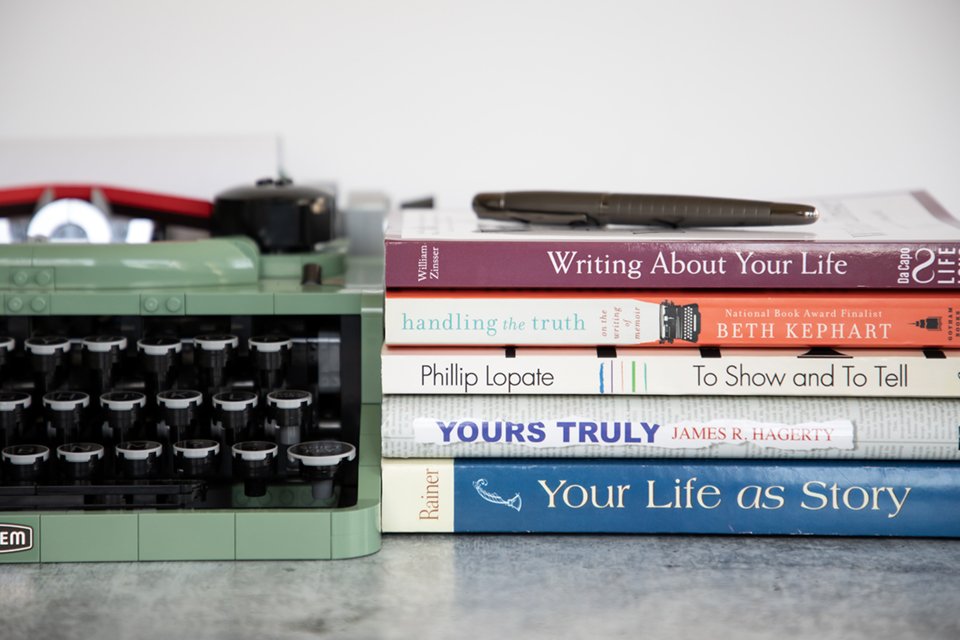

William Zinsser (who wrote my all-time favorite book about autobiographical writing, Writing About Your Life: A Journey into the Past) put it this way when describing a life story book his father left to him:

“Not being a writer, my father never worried about finding his ‘style.’ He just wrote the way he talked, and now, when I read his sentences, I hear his personality and his humor, his idioms and his usages, many of them an echo of his college years in the early 1900s. I also hear his honesty. He wasn’t sentimental about blood ties, and I smile at his terse appraisals of Uncle X, ‘a second-rater,’ or Cousin Y, who ‘never amounted to much.’”

He just wrote the way he talked.

When drafting your own life stories, write the way you talk, I implore you. Let your loved ones hear you when they read your memoir. Give them the gift not only of your memories, but of your voice, too.

3 ways to know your memoir voice is your authentic voice

Read a few paragraphs aloud without getting tripped up.

If you stumble over pronunciation or find the rhythm wonky (too many commas? too many long sentences?) then you’ve lost your voice. “If you’ve gone wrong, tried in print to be something you are not in life, the phrases feel like marbles in your mouth,” Anna Quindlen says in her book Write for Your Life. “But if you’ve gotten your own voice down on the page, you will read aloud and think: ‘Yep, that’s it. That’s me.’”

Leave your thesaurus in another room.

If you’re constantly looking up ‘better’ words, chances are they’re not words that would normally come out of your mouth. You’re not trying to impress your audience (most often, your family and descendants); you are trying to reveal yourself to them in new—honest—ways.

3 - Edit for clarity and impact only.

Don’t rewrite your sentences to make them sound overly polished or ornate. Don’t edit with an editor or teacher in mind, but with an audience of loved ones: Read your stories and ask yourself, Is this how I talk? Is my personality there? Is the STORY compelling/interesting/funny/engaging/memorable? Edit your work so the answers to those questions are, ‘yes!!’.

Oh, and the easiest hack to writing life stories that maintain your true voice? Speak your stories into a recorder, then transcribe (and lightly edit) them later.

If you write with an authentic voice, your readers will be captivated by you—your words, your stories, you.

Go beyond labels with this powerful memoir prompt: introduce yourself without name, job, or age. Includes writing tips and a free downloadable worksheet.

The three most common excuses I hear for not writing about your life “yet,” and how—and why—to overcome them. It’s not too soon for your memoir, I promise.

Discover how (and why) bending certain grammar rules in memoir and life story writing can enhance voice, rhythm, and authenticity in your storytelling.

Even the most seasoned writer sometimes feels hopeless when they sit down to write and nothing comes. Here, 7 helpful resources for budding memoirists.

Four steps to help you turn spoken stories into engaging written narratives—so once the family history interview is done, you can create a lasting legacy.

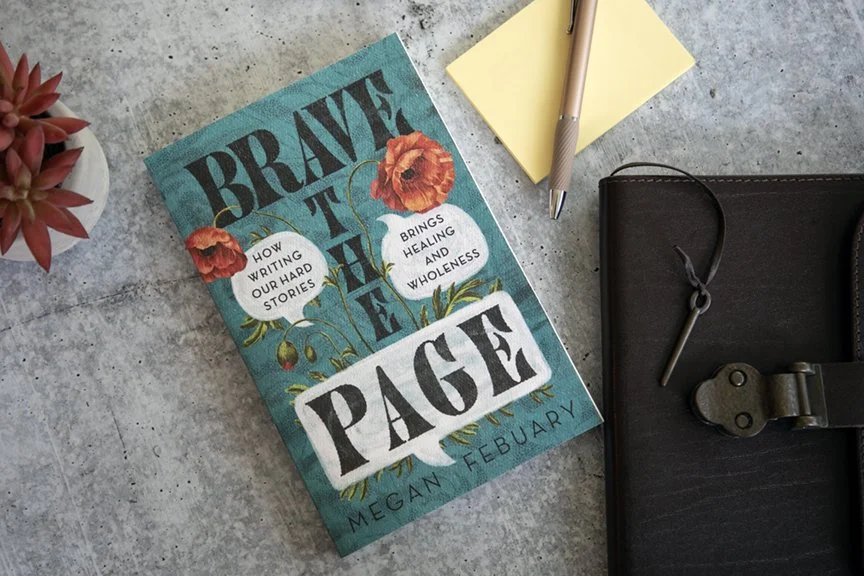

Brave the Page by trauma-informed writing coach Megan Febuary shares how to probe memories, write about your hard experiences, and find healing.

You start out with excitement and fervor—blank pages are feverishly filled with stories about your life. But what can you do when your memoir momentum wanes?

By holding as your goal the idea of ‘writing your memoir,’ you are focused too soon on the end goal. Instead, think about writing towards your memoir.

Are you nervous about undertaking a life story project? Working with a personal historian or memoir coach can help alleviate many of the most common fears.

Is there ever really a ‘right’ time to start writing your memoir? There’s not, in my opinion, but here are two questions to ask yourself to help you decide.

Writer’s block can happen to the best of us. This simple idea—keeping a notebook of self-generated writing prompts—will keep your memoir ideas flowing.

Looking for a meaningful gift for your parents? An annual subscription to our Write Your Life memory and writing prompts may be just the thing—or, maybe not.

Learn about our Write Your Life course, providing memory prompts, writing guidance and a dose of inspiration to anyone who wants to preserve their stories now.

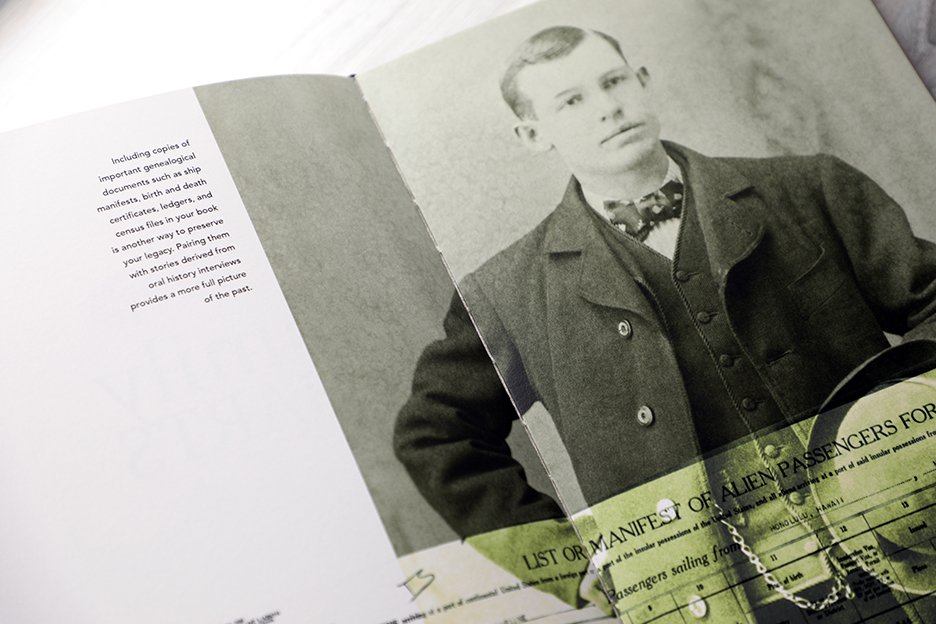

Here’s one time I gave in to my client’s preferences that still haunts me: Why we did not identify people in any of the photos in their family history book.

While your memoir is telling your stories in your words, a family tree chart outlining your relationships has a real place in that book—here’s why.

The first draft of your life story is likely to include some stuff you decide to cut later—but should none of your challenges make it into your final book?

Good writing prompts will rid you of blank-page anxiety—and you can easily write your own! Here, 5 steps to drafting a library of personalized memoir prompts.

While a journal called “Memories from Mom” or “Grandma’s Life Story” may be brimming with good intentions, the fact is that most of them remain mostly blank.

While all five of these books add value to any memoirist or life writer’s library, I’ve identified which is best for you based on your goals and experience.

A love letter (or book!) overflowing with memories makes a thoughtful anniversary gift. Here, 14 writing prompts to help you honor—and surprise—your partner.

Wondering if 52 weeks of memory prompts will help YOU write about your life at last? Here, answers to the most commonly asked questions about Write Your Life.

Every week you’ll get themed prompts to stir your memories, tips to write your stories with ease, and more! A unique gift for your loved one (or yourself)!

Sometimes all it takes to get unstuck with your personal writing is paying attention. Here are some easy (fun) ways to come up with journal writing prompts.

Ready to edit your family history or life story book? Follow these three tips from a personal historian to ensure everything is clear for your descendants.

This new book by Ruta Sepetys, You: The Story, is a great tool for those who want to use their own life experiences to inform their fiction writing.

Have you ever thought about what will happen to your diaries—who will read them, how you may one day use them? Join me as I consider this profound question.

Photos that have no captions will leave readers of your heirloom book guessing. Make sure to write captions that either tell a story or provide vital details.

Smells (such as of Mom’s perfume or Grandpa’s grease-stained clothes) and sounds—especially music—can trigger long-buried memories helpful for writing memoir.

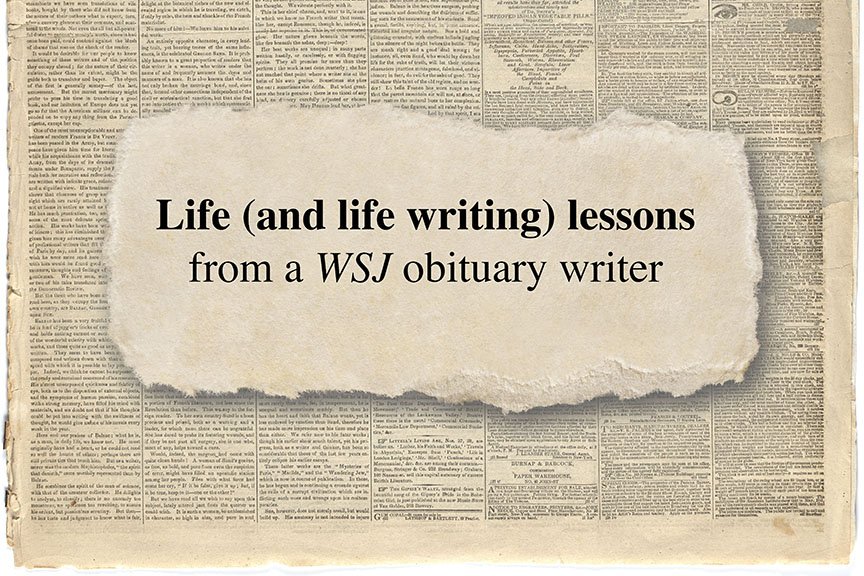

Why leave your legacy in the hands of someone else? Try your hand at writing your own obituary with these tips—it just may be the start of your mini memoir.

Stay inspired with 52 weekly writing prompts for journaling and family history. Capture memories, dreams, and stories big and small. Bonus: Downloadable guide!